Today we’d like to introduce you to Cassandra Quave.

Why did you want to tell your story with this book?

Born with multiple congenital defects of my skeletal system, expectations for my life’s path were quite low from day one. The main hope my parents and doctors had was that I could someday walk. Despite the odds, including a brush with death from a serious hospital-acquired infection at the age of three, I did learn to walk and eventually run, and then travel to places in the world that most have never dared in the pursuit of my intellectual passions. I wanted to tell this story, the journey of my life, in my own words with the goal of inspiring others to become empowered to chase their passions through building internal resilience.

At the same time, I wanted to tell my story with brutal honesty of the very real struggles and challenges of living with disability and chronic pain from my scoliosis and hip dysplasia. I am wary of falling into the trap of feeding into a classic disability trope—aka inspiration porn of being inspirational just because I exist as a disabled person or the disabled superhero or super-athlete trope. Strangely, many people who see me wearing a prosthetic leg assume I can run like an Olympian with blade-legs they’ve seen on TV. My usual retort is “no, can you run that fast?” I am no athlete. My hope is that this memoir can serve as a window into the real life of someone with very real challenges and no superpowers, just a positive attitude and a willingness to fail and get back up to try again.

I also wanted to take this opportunity to educate the public both about the very real dangers of emerging antibiotic resistant superbugs. I’m in the biggest fight of my professional life today, working against the odds to find new pharmaceutical compounds to combat the superbugs that will fuel the next public health crisis. There is tremendous pharmacological potential in traditional remedies derived from nature, and this is where I believe we’ll find the next lifesaving medicines.

What made you want to become a scientist and the study of plants in particular?

The periods of limited mobility I experienced as a child gave me the time and space to slow down and really observe life closely. Growing up in the countryside in a rural small town in Florida, I was surrounded by wildlife and spent many days perched in the branches of an old oak tree watching birds and observing insects that swam around inside the small pools of water found in epiphytic bromeliads. I was a curious child with a vivid imagination. The possibilities of the unseen world—that of microscopic creatures found in the water—really captured my interest. While I couldn’t really participate in sports in school, my passion for observing the natural world was reinforced by my success in school science fairs, and science soon became my sport.

My interests long vacillated between science and medicine, but it wasn’t until my junior year of college that I finally experienced that “aha” moment when I read about ethnobotany—the scientific study of the relationships between people and plants. My interest in the connection between medicine, nature, and culture was further bolstered when I experienced both the power and limitations of traditional medicine during my time in the Peruvian Amazon. It was in the Amazon that I realized that instead of practicing medicine as a physician, I wanted to discover and develop new medicines inspired by nature.

What advice would you give to young girls looking to go into STEM, but are nervous about being in a traditionally male dominated space?

I think my story is relevant not only to young girls and women interested in science but also to anyone “other” that doesn’t fit into the majority white male category—black, Indigenous, and people of color, disabled, and LGBTQ individuals. First, it is valid to feel nervous; there are systemic barriers that you will face. But, the good news is that things are changing and these biases and barriers are becoming more widely recognized for being what they are: wholly unacceptable and disruptive to innovation and progress in science. In my experience, building a network of friends, allies, mentors, and sponsors is critical to your success. You can commiserate with friends, allies will stand up for you when you need it most, mentors can provide valuable advice, and sponsors can lift you up through nominating you for opportunities you may not even be aware of yet.

You’ve juggled a lot of obstacles to get to where you are; your disability, being a female in a male dominated space, money struggles, juggling being a new mom during all of it. Out of all of it what was the hardest obstacle and how did you get over it?

My obstacles have varied depending on the different stages of my life. There always seem to be hurdles and after I clear one, I have to dig deep for the energy to surmount the next one. It’s the relentlessness of the obstacles that has been the hardest to address. You don’t have to be disabled or a working mom to experience this.

You have studied hundreds of plants in your life, does one stand out to you or is there any plant you particularly love or are fascinated by and why?

This is such a difficult question to answer as there are so many plants that I love for different reasons. When it comes to trees, I’ve always felt a sense of awe in the presence of Yew trees. Their wood was used to make the legendary longbows and the trees also produce cancer battling compounds that have saved the lives of countless patients battling breast, ovarian, pancreatic, cervical and lung cancer. I’m an unabashed tree hugger, and on a trip to Scotland I had the opportunity to see (and hug) the Fortingall Yew, located in a small churchyard in the countryside. This particular yew tree is thousands of years old; some estimate it to be more than 5,000 years old, living before the Great Pyramids of Giza were built! It is a powerful thing to wrap your arms around such an ancient creature.

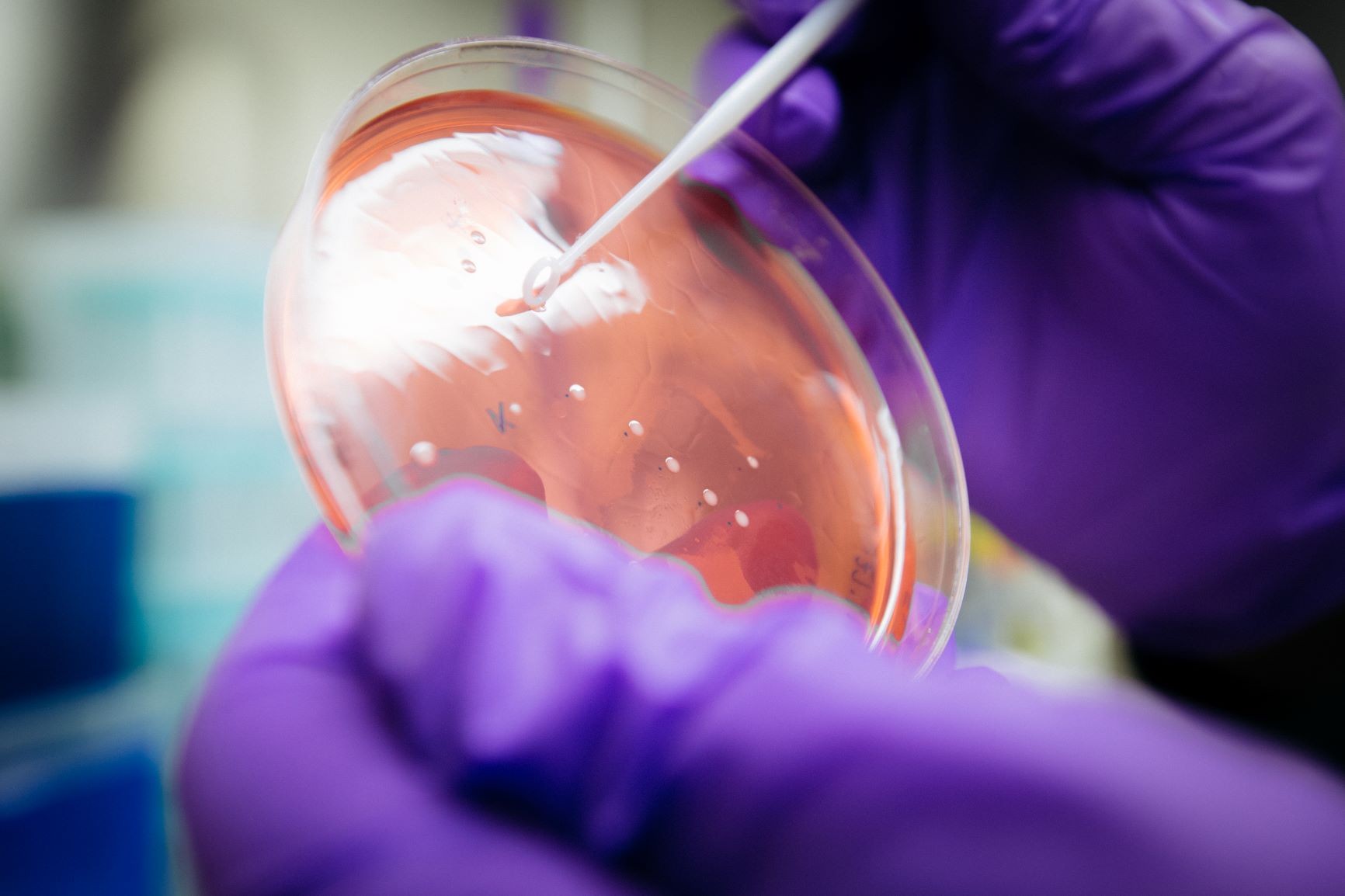

In my lab research, I’ve become increasingly fascinated with the medicinal potential of the Brazilian peppertree. It’s an unusual choice for most as it is a hated weed in my home state of Florida, but we’ve found texts in Latin going back to the 1600s that extoll its value as a medicinal ingredient for a variety of ailments, including the treatment of wound infections. In my lab, we’ve discovered that certain compounds from the peppertree fruits can work to remove the toxin-producing capabilities of deadly MRSA bacteria, drastically reducing their ability to cause harm. We’ve also found an antibiotic compound in the peppertree leaves that can combat superbug bacteria and even fungi, like Candida auris.

What do you want the everyday person who doesn’t have as strong of knowledge of ethnobotany to know about the plant world?

Many of us don’t really see the natural world. This condition is known as “plant awareness disparity”. Ethnobotany is the gateway to recognizing and building relationships with plants. Plants affect us in innumerable ways—from the food we eat to the medicines that heal or the fabrics that clothe our bodies. More than 33,000 plants have been used in traditional medicine, yet despite this rich history, modern science has barely scratched the surface in studying their pharmacological potential. I’d love to encourage readers to take some time to get to know the plants that benefit their lives everyday—whether as sources of food or clothing or even in ornamentation used to decorate the home and landscape.

You’ve worked with a lot of mentors along the way, some more grounded in the scientific world and others in the spiritual world. How did you combine these two worlds in your work?

My didactic training has been in a hard science background, but my lived experiences have led me to appreciate that medicine and health are multidimensional and that not all of science or medicine can be fully understood with standard Western approaches alone. Throughout history, some of the game-changing paradigm shifts in how humans see the world came only after centuries of experiments and careful documentation by numerous researchers, often at great personal sacrifice of those scholars. Take for example germ theory: at one time it was unfathomable that tiny creatures invisible to the naked eye existed, much less could enter the human body and cause disease! There are aspects to traditional medicine, especially those that embed spirituality in the practice, that are not easily explained by Western science. As a point of practice, I work diligently to record details and gather all of the data that I can when investigating a particular herbal practice, but I also do so knowing that we may not have all of the right scientific tools or even the ability to ask the right questions of their pharmacological activity at this moment in time. Humility and keeping an open mind is key in this field of research.

You’ve traveled all over the world for your research. Can you tell us about any community and their use of a plant that surprised you?

When it comes to the most surprising herb, one that immediately comes to mind is catnip. This is commonly sold in plant nurseries and hardware shops, and while I knew of the affinity that cats have for the herb, I’d never read about human uses. I became fascinated with the calming effect of catnip, a member of the mint family, during one of my research expeditions in the Balkans. The Gorani people bathe their children in warm baths with the herb and drink a tea of it to treat fright, nightmares, and anxiety. Whenever I’m feeling a bit stressed or anxious, I brew up a cup of catnip tea grown in my garden, often blending in a bit of lemon balm as well, and sweeten it with some honey: a delicious and calming brew!

Appreciate you sharing that. What else should we know about what you do?

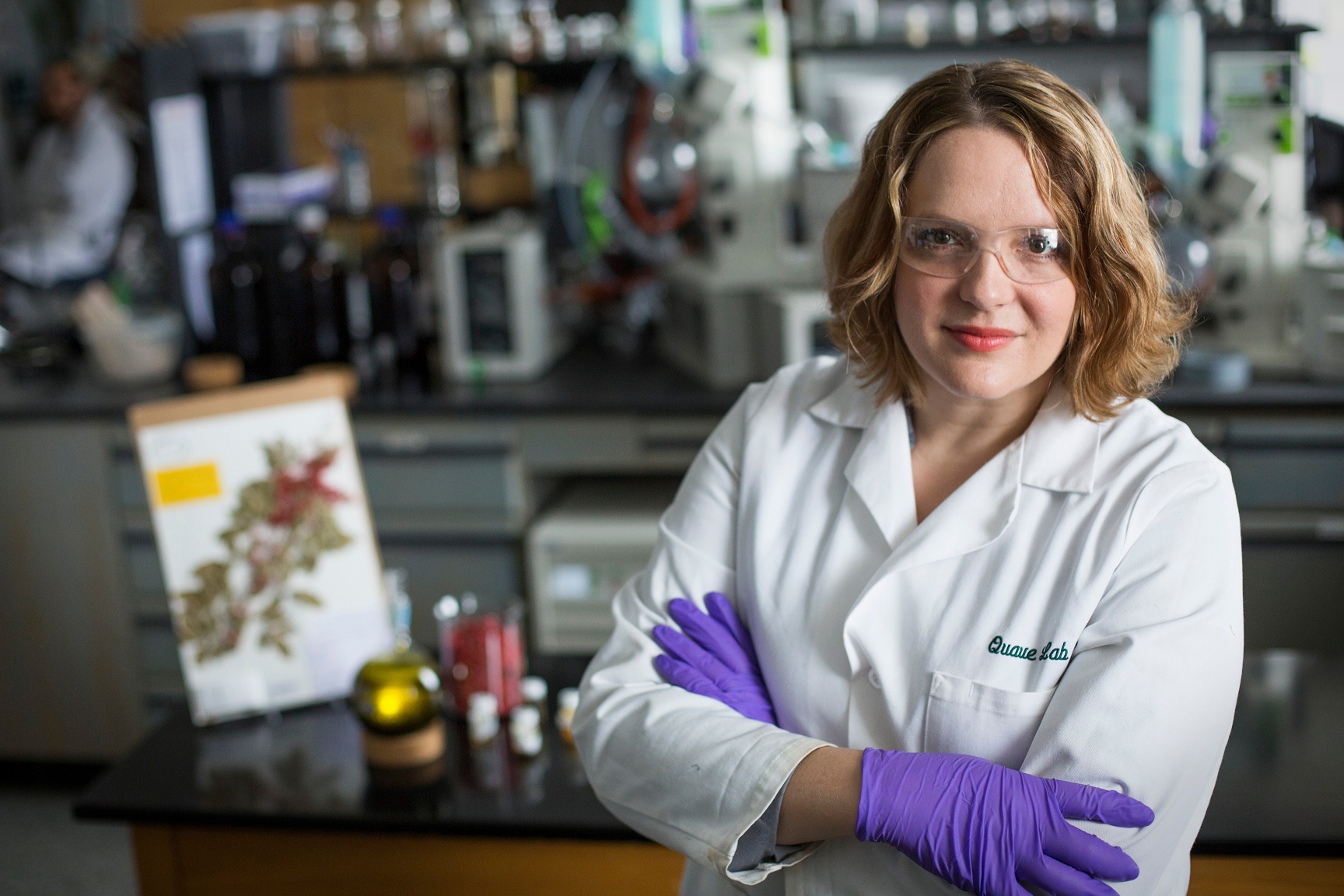

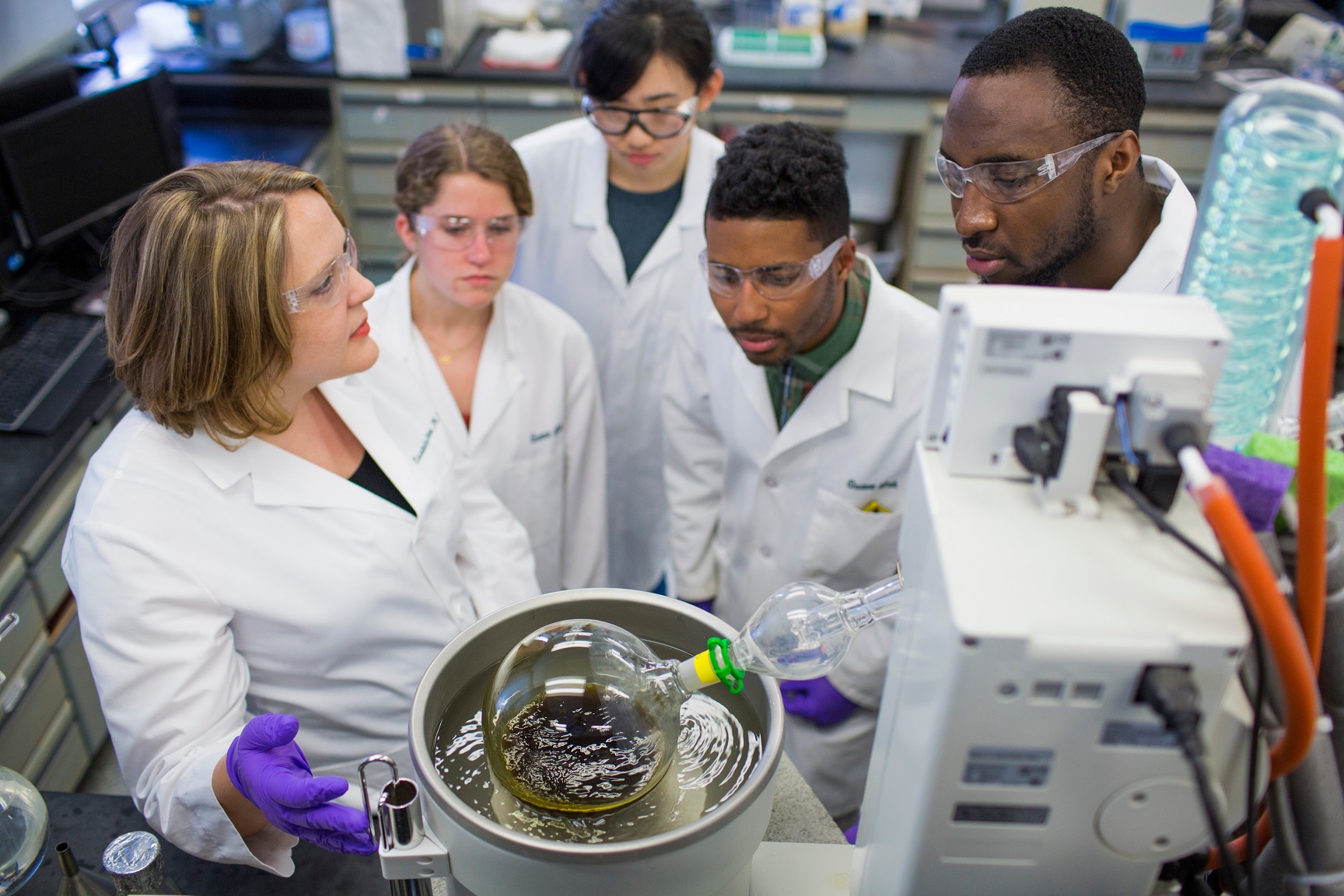

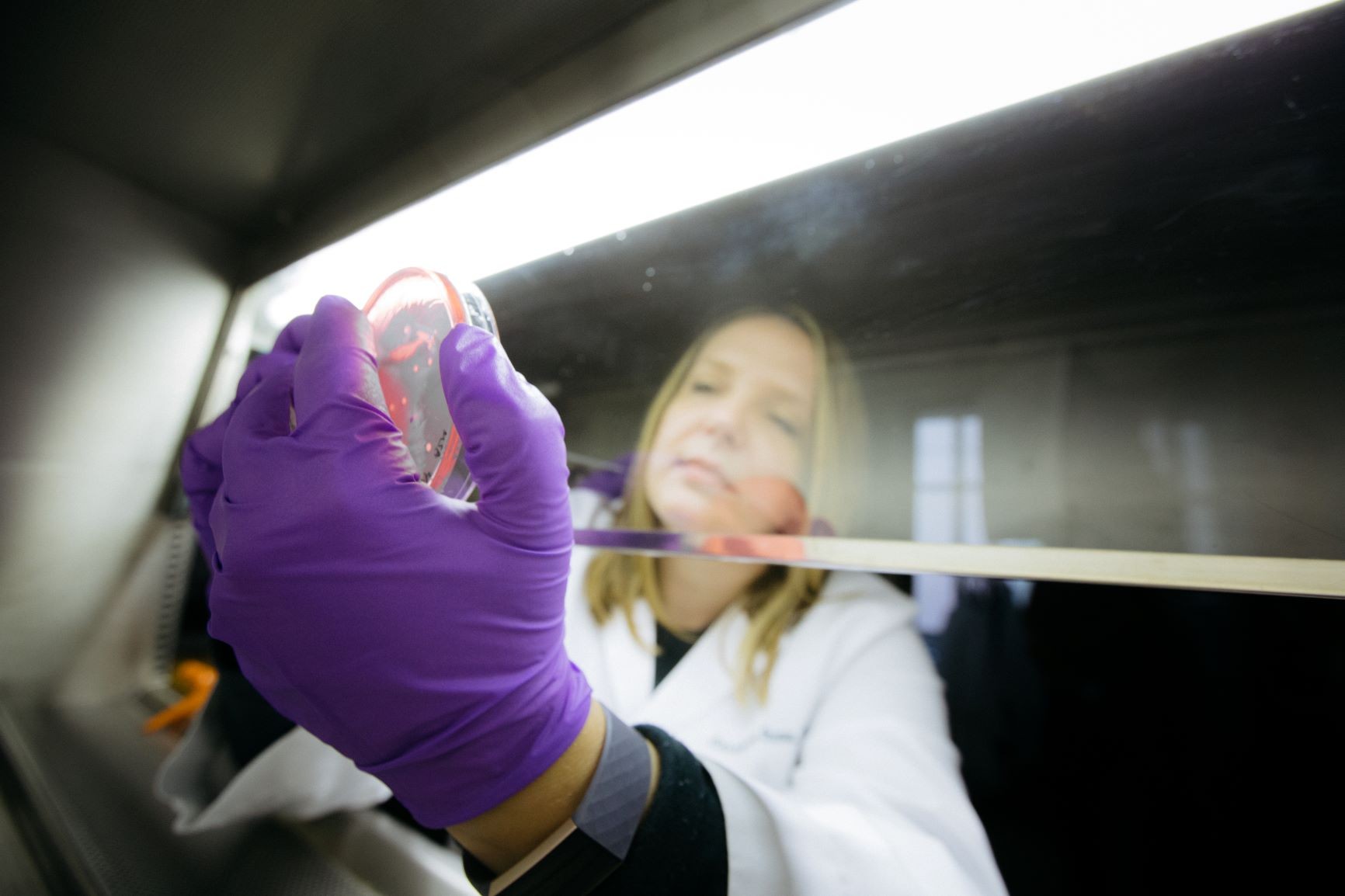

I’m a scientist and author. I run a research group at Emory University that is dedicated to the study of medicinal plants used in traditional medicine for the treatment of infections. We investigate the pharmacological potential of these plants. In my new book, The Plant Hunter (Viking, 2021), I take readers on the journey of becoming a scientist and undertaking research on plants around the world.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://cassandraquave.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/quaveethnobot/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/QuaveMedicineWoman

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/QuaveEthnobot

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/TeachEthnobotany

- Other: https://etnobotanica.us/

Image Credits:

Emory photo/video for all photos except the last one with my book sign. That one is by Marco Caputo