Today we’d like to introduce you to David Petrides.

David, can you briefly walk us through your story – how you started and how you got to where you are today.

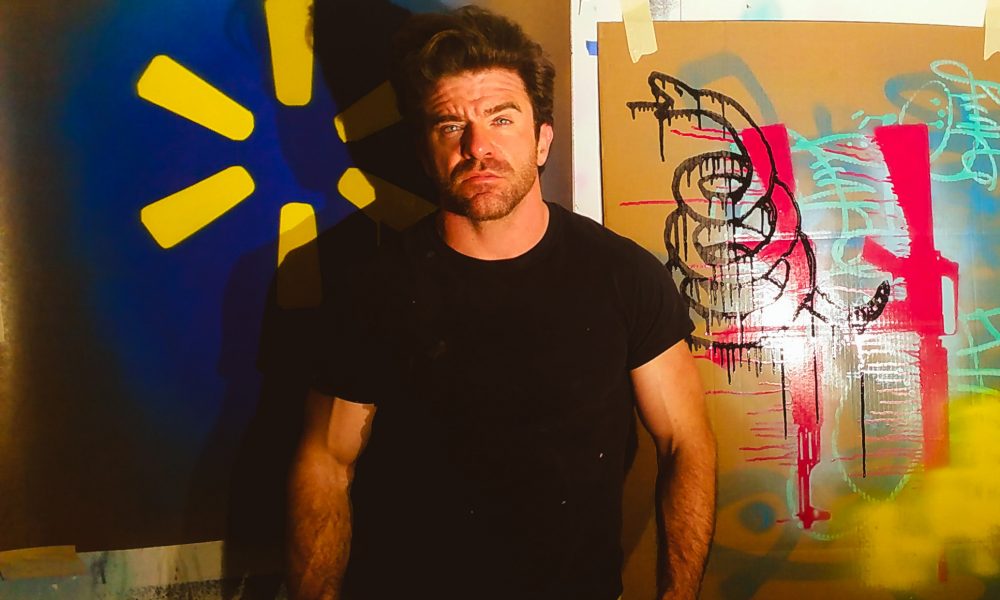

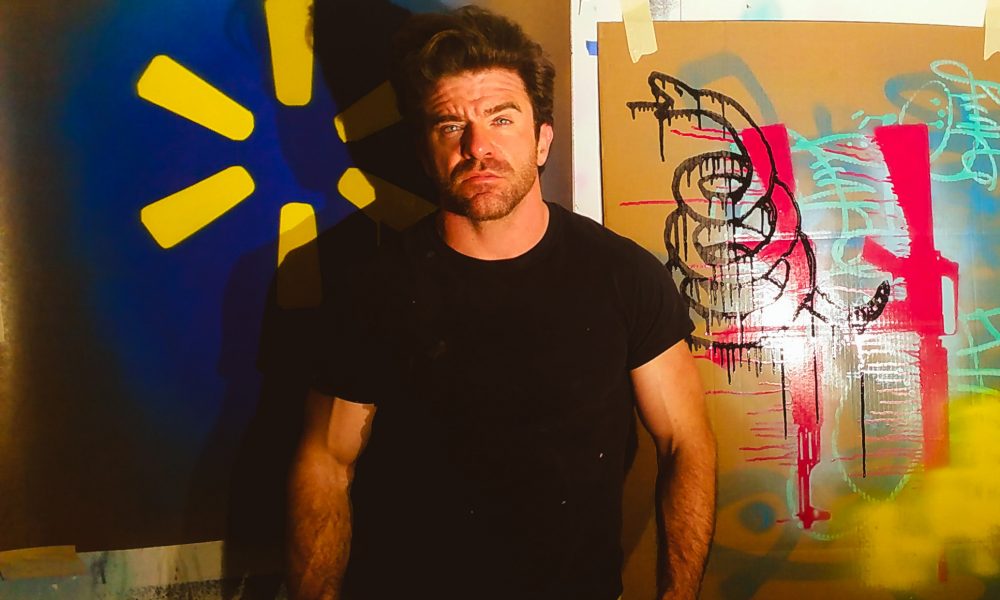

To my surprise, I was born in the South. My childhood was spent — or maybe invested — playing with Legos. It’s basically all I did. I was a pale, fragile, artsy nerd. I stayed that way on the inside, I guess, so it wasn’t much of a stretch to pursue an arts major at a nerdy college. I attended the Industrial Design program at Georgia Tech in the late 90s. I hated it the whole time. After I got out, I abandoned an idea of entering the white-collar workforce and I became a woodworker. I was lucky to be able to train under master chairmaker Michael Gilmartin and I eventually started a furniture design studio, which was annihilated by the economic downturn. Seriously, completely crushed. I spent the next several years learning how to be a better capitalist. Eventually, managed to monetize my sculpture, metalcraft and woodworking talents by founding a manufacturing company — Gearheart Industry — that makes woodburning equipment. We make custom precision branding irons for artists and craftspeople literally all over the world.

Yeah, I own a business, but I consider being my art to be my full-time job. I’m in my studio in Tucker seven days a week, whether I feel inspired or not. I have days where every single thing I create is garbage, which is difficult to deal with but every day, I grind pays dividends when things align. Have you ever been driving late at night and you find yourself alone on a stretch of road where you can be seen all the traffic lights in front of you? And they all turn green, green, green, the whole road opening up, not a red in sight and you just feel… unlimited? That’s a good day in the studio. The bad days — maybe they’re necessary. The good days are worth it.

Has it been a smooth road?

It was a bit dicey at times. My transition to adulthood was a bit like suddenly being plopped into the seat of a tremendously complex, dangerous machine with a copy of the user’s manual and a pat on the back. I had a solid command of a truly massive amount of TOTALLY USELESS knowledge and a moral compass informed by a belief structure that, although it had been pounded into my skull, made very little logical sense to me. My lack of identity and direction contributed to a lot of really stupid decisions.

I was a tornado, a danger to myself and others. I was fueled by rage, self-hatred, apathy, depression, impulsiveness. I was traumatized and I inflicted more than my share of trauma, too. I didn’t flirt with criminality and lunacy… I went steady with it.

If my life were a morality tale, it’d have ended tragically, but that’s not always the way things work out in real life, is it? More often than not, there’s no big showdown, no sudden redemption, no epiphany. I just ran out of energy over time and it forced me to look around and take stock of who, and where I was. WHAT I was. I gradually realized I could be whoever and whatever, I wanted — I didn’t need to ask permission, I just had to seize my agency.

To a large degree, I don’t have any regrets, though. Everything I was, I still carry with me — bad decisions and unpleasant situations are very useful for developing a unique perspective. I don’t regret the rough years and I don’t resent the fortunate ones that have followed. So next week, when I’m wielding a paintbrush or a can of spray paint, or a plasma cutter, I’ve got an amazing palette of experiences that I can dip into, mix, synthesize.

It hasn’t been easy or fun. But I wouldn’t change a thing.

So let’s switch gears a bit and go into the side of being an artist story. Tell us more about the business.

The most interesting — terrifying, exhilarating — parts of our world exist at the borders and boundaries, particularly where those lines and surfaces are transgressed. My artwork simulates this violation; the violation of my body and spirit, the violation of our culture and the human experience, the violation of nature and invention. Most of my photography, for instance, document juxtaposition and struggle: the uneasy interface between interactive structures and abandonment — playground equipment at night, for instance — or clashes between economic classes, as seen in my exploration of graffiti in Ushuaia, Argentina. My paintings and sculpture dissect similar themes: the penetration of organic structures in my Wound Dynamics series or my current street art project coupling right-wing nationalist emblems with corporate logos and slogans.

I employ the semiotics of industrialism and western capitalism in a subversive manner to inspire discourse about what it means to be an individual and a human. Through the use and misuse of modern manufacturing processes, I explore the conflict theaters of transhumanism, AI, automation and I trace those onto the smaller, more intense battlegrounds of sexuality, spirituality and personal violence. I don’t see myself as a cultural observer — I recognize that I’m an ecstatic participant. I fetishize American power structures with the understanding that by worshiping them, I can simultaneously expose them to blaspheme and ridicule. In a way, it’s cathartic, and in another sense, it’s self-immolation. Cultural arson. I embrace it — Walmart, politics, avarice — but I’m on fire.

How do you think the industry will change over the next decade?

Regarding my literal industry — boutique manufacturing — I certainly have an opinion. I could pontificate for AGES about additive machining, automated work cells, robotics, offshoring and a million other topics. Gearheart Industry is a pretty nimble organization and we’re incredibly efficient and capable of pivoting far more quickly than our competitors. I’m pretty confident that in 10 years we’ll still be a leader in our field.

As far as art goes, I think it’ll actually mirror the changes that I’ve already been dealing with for a while in the manufacturing sector. I predict we’ll see fewer successful artists opting for the workshop-full-of-assistants factory setup, a la Burden, Koons, Hirst or Warhol and more individuals embracing the force multiplier of technology, specifically automation. CNC equipment, including 3D printers, have MASSIVELY increased the productive capability of artists, especially since the controls have become less industrial and more suited to non-specialized users. Advances in communication and real-time collaboration enable artists to realize projects that just 10 years ago would have required grants and generous patrons. And increasingly ubiquitous digital tools like iPads and digital cameras enfranchize more and more new artists every day.

Sure, it’ll mean more competition — but remember, I’m a capitalist. Competition is a GOOD thing.

Contact Info:

- Website: davidpetrides.com

- Email: art@davidpetrides.com

- Instagram: @davidpetrides

Getting in touch: VoyageATL is built on recommendations from the community; it’s how we uncover hidden gems, so if you know someone who deserves recognition please let us know here.