Today we’d like to introduce you to Jimmie Henderson.

Hi Jimmie, we’d love for you to start by introducing yourself.

I am Jimmie Conle Henderson and I am a community-rooted organizer, peace advocate and emerging legal scholar shaped by the layered histories of Savannah, Georgia. Raised in a region marked by both the scars and the strength of Black Southern resilience, my worldview was formed at the intersection of faith, family, and struggle. I come from people who know how to make a way out of no way, who taught me that justice isn’t a distant theory – it’s a daily responsibility. My upbringing was deeply impacted by witnessing structural inequalities – whether in underfunded schools, unsafe streets, or the undervaluing of essential workers. But it was also full of beauty: intergenerational wisdom stored in the Spanish moss native to Savannah and elders who organized and advocated for themselves and more so me and my future. My sense of self was tested early. My mother passed away on my fourth birthday, a loss that reshaped everything. My aunt stepped in to raise me, but her time with me was also cut short when she passed away not long after. For a while, it was my cousins who raised me – not as a distant relative but like I was their little brother. My oldest cousin Nella took the lead. Though she lived with physical disabilities, she never let that define her or lower her expectations for me. She was the one who instilled in me the importance of education, independence, and confidence. I remember sitting at our dining room table doing homework, if my handwriting wasn’t up to par, the work was erased even if right. I’d cry when after already doing homework, I had to read a chapter of a book or news article aloud. At the time, I didn’t get it. But now I know that’s where my academic discipline was born. That’s where my voice was first sharpened.

We shared laughter, too – watching Big Brother together every summer, having debates about houseguests like we were political commentators. I remeber the day the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage, I also remeber how deeply we grieved after the pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida. These weren’t just news stories; they shaped how I saw the world and how the world saw people like me. Because Nella was disabled, I had to grow up fast. I wasn’t treated like a child – I was treated like someone who needed to be ready. Ready to care, to step up, to lead. That responsibility shaped my understanding of manhood, love, and justice more than anything else. Growing up in Savannah meant being surrounded by history every day. The city is known for its cobblestone streets, historic homes, and big oak trees draped in Spanish moss – but for me, it was the people who made it feel like home. I grew up in a close knit Black community where neighbors looked out for each other, where Sundays were for church and a good meal, and where front porches were stomping grounds for spades and seafood nights. There was always a sense of pride in where we came from, no matter the economic inequalities of the time. You didn’t have to look far to see the impact of underfunded schools, neglected neighborhoods, or people working hard to survive. Despite that, there was a strong culture of care, creativity, and resistance. Savannah taught me what it means to be rooted in community, and to carry both the joy and the responsibility that comes with that. One of the earlier memories that shaped my sense of purpose was watching my family and neighbors ban together, mobilize and ignite action after Hurricane Irma in 2017. I saw firsthand that organizing wasn’t just about politics – it was about love. I saw firsthand that you don’t need some community leader to swoop in and save the day, that I was the community leader.

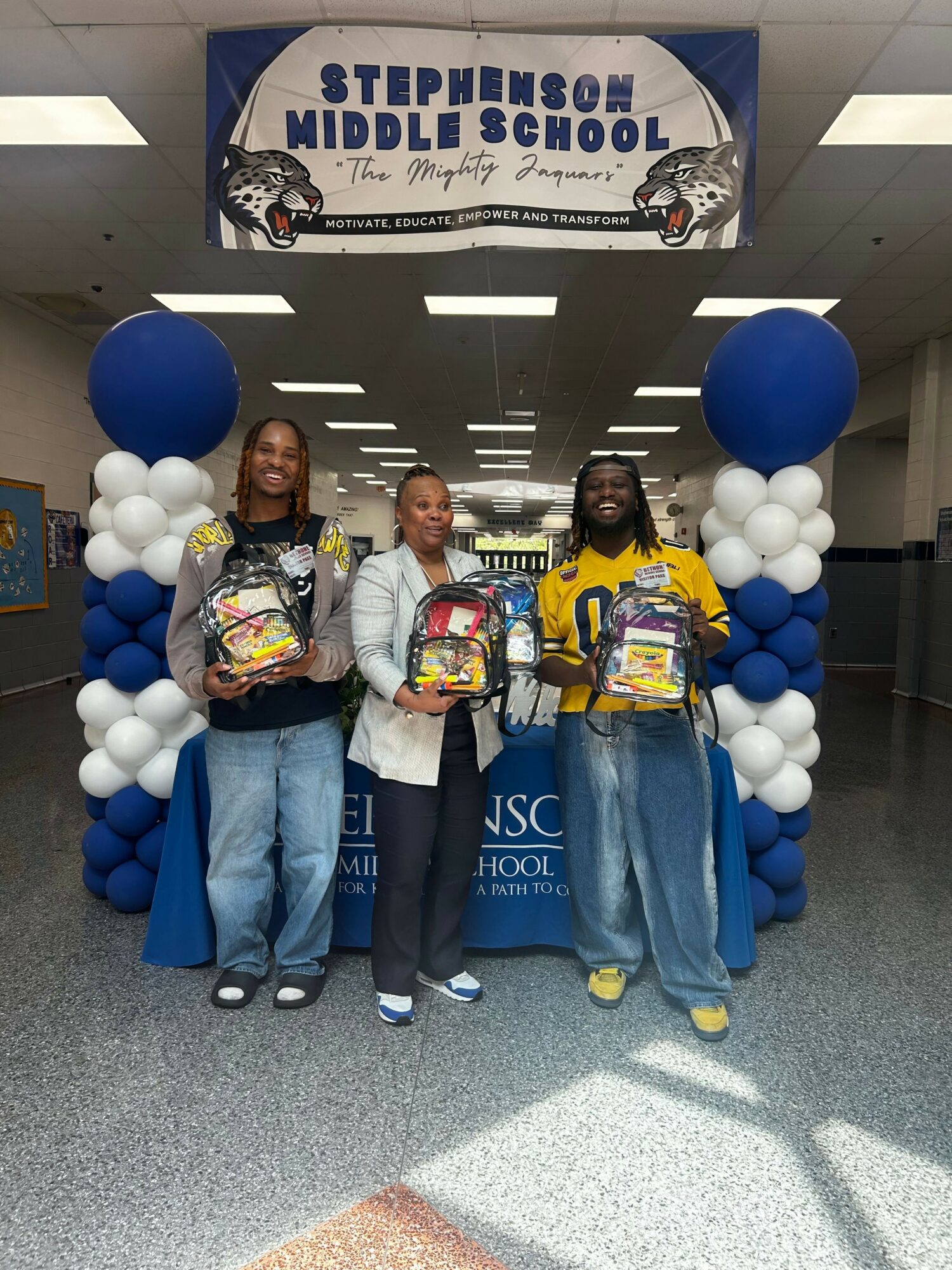

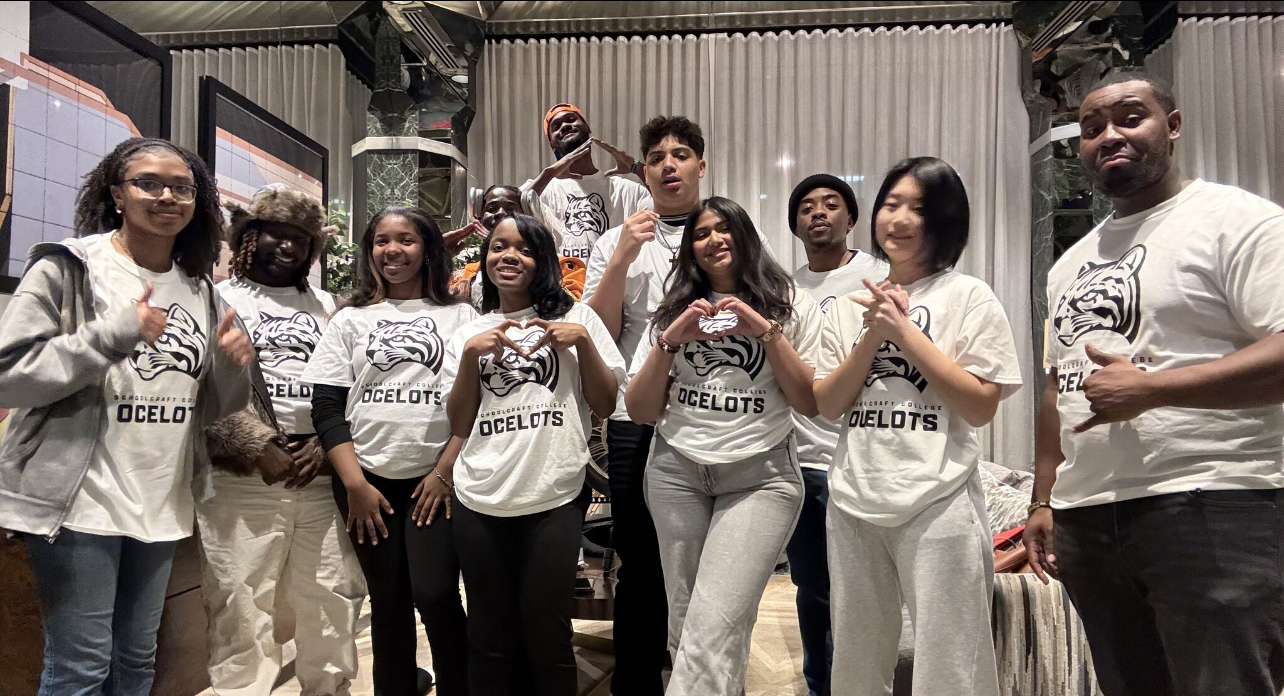

Today, I am a youth advocate and peacebuilder focused on nuclear disarmament, labor justice, and transformative education. I organize because I believe our collective survival depends on both dismantling violent systems and imagining something radically better. As a PEAC Institute Fellow, I’ve had the privilege of engaging in global disarmament work rooted in solidarity with survivors, students and storytellers. From mentoring youth delegates at the United Nations to co-leading community centered events with Back from the Brink Atlanta Hub, I am committed to shifting culture and policy alike. My work didn’t begin with disarmament. It began in labor organizing – listening to workers and fighting for dignity on the job. More specifically, it began with a summer internship through the Southern Summer Institute for Worker Justice hosted at Morehouse College. That was my introduction to the deep legacy of Black labor organizing, not just as a concept in a textbook but as a living, breathing movement still in motion. We weren’t just learning from behind the desk; we were in the streets, protesting exploitative labor practices at Amazon and Starbucks, and listening to stories from workers fighting for dignity, wages, and safety. It was there I met Jahrik Browner, a fellow participant who saw something in me early on. He recognized how deeply I cared about politics, policy and diplomacy, and invited me to help out with a new campaign initiative in the Atlanta area – Students for Nuclear Disarmament. So yes, my initial interest was a favor for a friend turned so much more! That small amount of mutual respect and belief would change everything.

Would you say it’s been a smooth road, and if not what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced along the way?

I have always been the one who spoke up when something felt off. Whether in a classroom, a protest, or a meeting with UN diplomats. But before I ever had the language of advocacy, policy, or organizing, I was just a kid watching the world unfold around me. I didn’t grow up in a courtroom or around lawyers. I grew up in Savannah, Georgia. Around front porch debates, seafood boils, and people who knew how to make a way out of no way. I also grew up around structural inequalities: underfunded schools, overpoliced communities, and everyday workers undervalued for their labor. That contrast between care and injustice shaped me early. But it wasn’t until later that I realized what I had always been doing had a name: advocacy.

My story starts with a lot of loss. My mother passed away on my fourth birthday. My aunt stepped in to raise me, but she passed not long after. So I was raised by my older cousins, kids themselves really – who became my first teachers. My cousin Nella, who lived with a disability, ran our household with love and structure. She pushed me to take school seriously. If my handwriting wasn’t legible, I had to erase it, even if the answer was right. I cried a lot at the table, especially after finishing homework only to be told to read a news article out loud. But looking back, that’s where my academic discipline and confidence were born. That’s where my voice was first sharpened. We shared joy too – debating Big Brother contestants like political strategists, celebrating the legalization of same-sex marriage, mourning together after the Pulse nightclub shooting. These weren’t just headlines, they were personal. Being Black and queer in the South meant I was constantly learning how to protect my peace in systems that weren’t built for me. I was expected to be a “good boy”, a “respectable man,” but what I really needed was to be seen fully, for who I was and who I was becoming. What I really needed was an advocate.

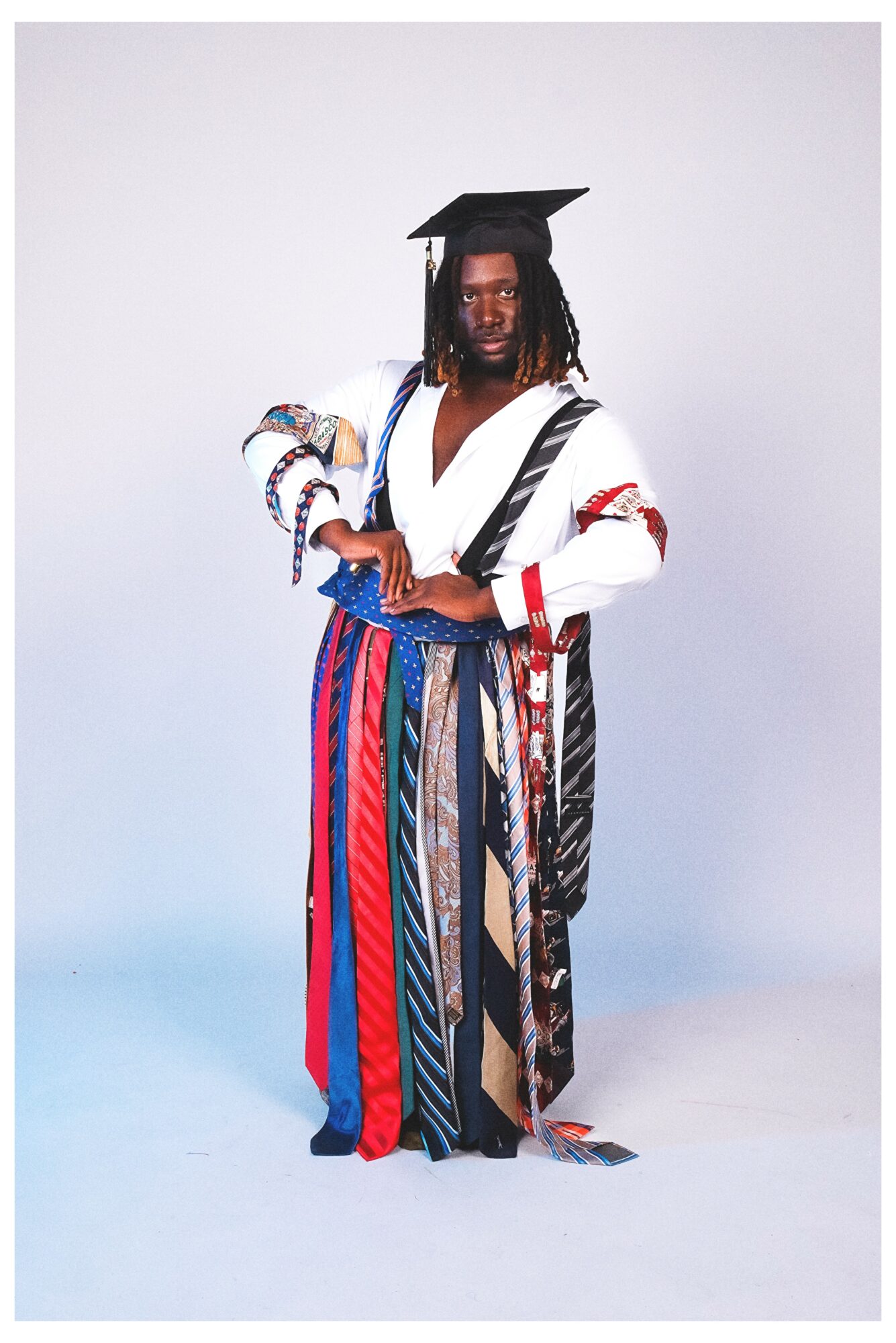

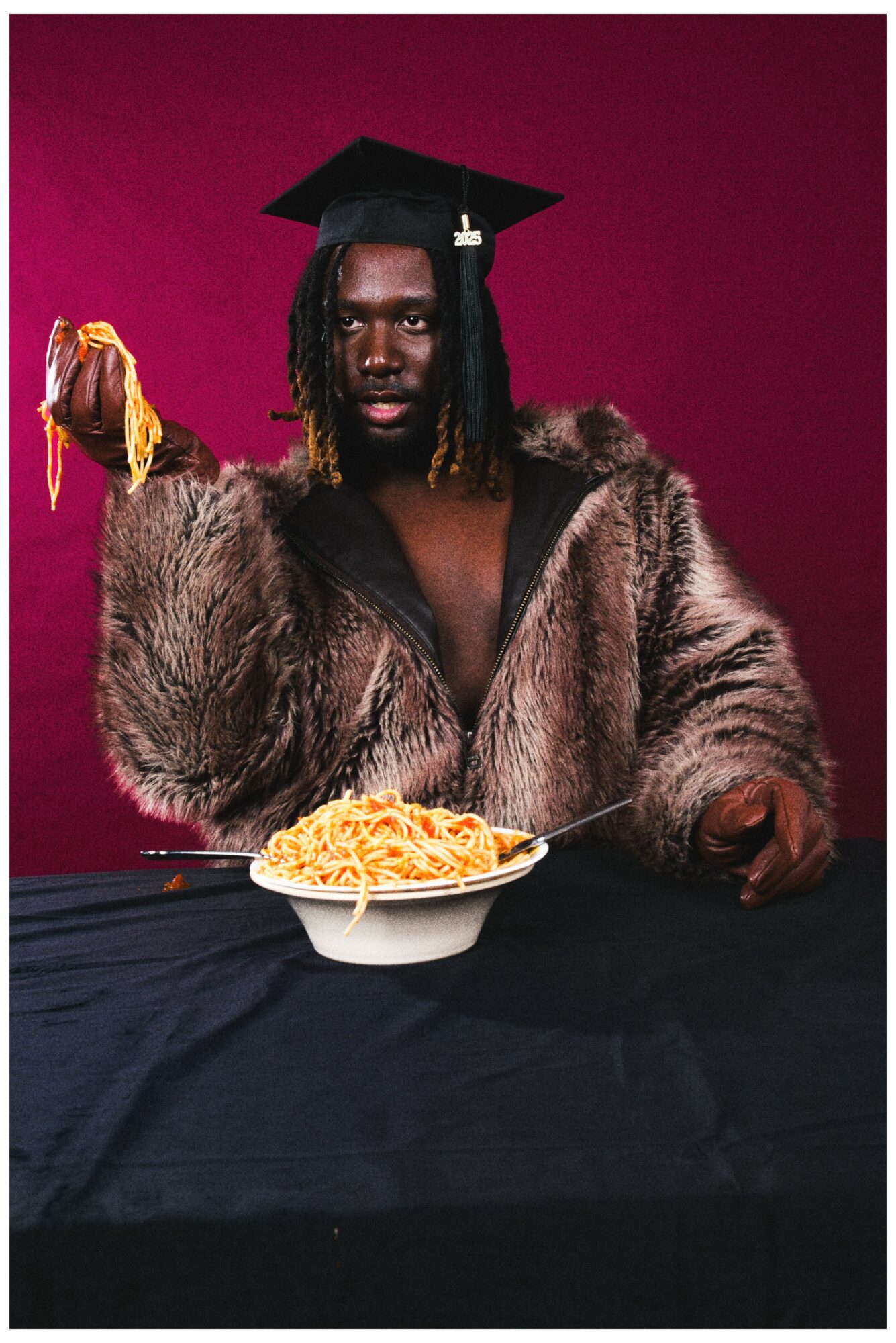

I didn’t come from money. I didn’t have access to elite networks or institutions growing up. But what I did come from was love – and that has carried me further than any resume ever could. I come from a family that didn’t shame me for being queer, but instead embraced me with warmth, laughter, and constant encouragement. My family always told me, “They can’t take away what’s in your head” – a reminder that education, knowledge and self-worth are forms of power that no system can strip away. My dad always encouraged me saying, “You smart enough to get yourself out of anything!” But I also came to understand that knowing something and being something are two different battles. While my family uplifted me, the world often asked me to shrink. To be the “good boy”, the “respectable man,” the palatable version of myself that wouldn’t ruffle feathers in white, cis, or conservative spaces. That’s where the real work began – unlearning those quiet demands and reclaiming who I was outside of who I was expected to be. Organizing and movement work didn’t just teach me how to fight systems-it helped me discover who I am. These past few years, filled with challenge, confrontation, and transformation, have made me more honest with myself than ever before. I’ve come to realize working on the world means working on myself. Knowing who you are – deeply and without compromise – is one of the most radical acts in a world that profits off confusion and conformity.

Can you tell our readers more about what you do and what you think sets you apart from others?

Today, I am a youth advocate and peacebuilder focused on nuclear disarmament, labor justice, and transformative education. I organize because I believe our collective survival depends on both dismantling violent systems and imagining something radically better. As a PEAC Institute Fellow, I’ve had the privilege of engaging in global disarmament work rooted in solidarity with survivors, students and storytellers. From mentoring youth delegates at the United Nations to co-leading community centered events with Back from the Brink Atlanta Hub, I am committed to shifting culture and policy alike. My work didn’t begin with disarmament. It began in labor organizing – listening to workers and fighting for dignity on the job. More specifically, it began with a summer internship through the Southern Summer Institute for Worker Justice hosted at Morehouse College. That was my introduction to the deep legacy of Black labor organizing, not just as a concept in a textbook but as a living, breathing movement still in motion. We weren’t just learning from behind the desk; we were in the streets, protesting exploitative labor practices at Amazon and Starbucks, and listening to stories from workers fighting for dignity, wages, and safety. It was there I met Jahrik Browner, a fellow participant who saw something in me early on. He recognized how deeply I cared about politics, policy and diplomacy, and invited me to help out with a new campaign initiative in the Atlanta area – Students for Nuclear Disarmament. So yes, my initial interest was a favor for a friend turned so much more! That small amount of mutual respect and belief would change everything.

That summer, I realized organizing wasn’t just about demanding better – it was about building relationships, studying history, and showing up even when the cameras weren’t rolling. The stories we heard from the labor union elders connected us to civil rights leaders, sharecroppers, sanitation workers, and domestic laborers who had laid the groundwork for every moment we benefit from today. Those lessons stuck with me. Labor Justice wasn’t just about work – it was about worth. Running into Steve Leeper, a long-time peace advocate and key figure in Hiroshima-based disarmament work, changed the trajectory of my organizing. I was introduced to Rebecca Irby shortly after. They saw how seriously I took this work, not just in theory, but in action-and invited me into spaces I had only ever imagined. Within a year of marching in Atlanta, I was sitting in diplomatic sessions at the United Nations as a youth delegate. But I never forget where I started, on the ground, listening to workers, writing protest chants, and organizing teach-ins. From there, the dots connected quickly. I began to understand that war abroad and exploitation at home are symptoms of the same system-one that devalues life for profit and control. My current focus is on building coalitions that refuse to see peace, justice and equality as separate fights. They all have a singular root; oppression!

My impact lives at the intersection of legislative disruption and grassroot healing. At Morehouse College, I helped coordinate high-profile peace events that connected Nobel Laureates with students. At the United Nations, I mentored youth navigating diplomatic spaces not designed for our voices. In Atlanta, I co-founded the local chapter of Students for Nuclear Disarmament to make sure the South isn’t left out of the conversation. My identity as a Black, Southern, queer leader shaped everything I do. I lead with empathy and strategy, and I’m most powerful when I’m in community. People have told me that I create space for reflection, honesty, but most importantly to me authentically themselves – after all that’s all I try to be, authentically myself. I’m humbled by the fact that I will forever be a student, knowing that I’ve learned just as much from high school students in workshops as I have from Nobel Peace Prize recipients in conference halls. Both matters. Neither is optional. Justice to me looks like systems that center care over control, healing over punishment and community over coercion. It looks like classrooms where ALL stories are welcome. Workplaces where every voice is valued. Governments that practice accountability, not just authority. I want to be a part of building that world and be among the emerging leaders of Gen Z as we come of age. Ten years from now, I want people to remember me not just for the positions I held, but for the people I held space for. I want to be known as someone who built bridges across race, class, age, sexuality, and nation. Someone who loved deeply and organized fiercely, all in impeccable style. I hope to continue integrating law, narrative and movement work to shift both policy and possibility. If I could redesign a system, I’d start with education. I’d build schools that prioritize liberation and creativity over discipline and standardization. I would equip every young person with the tools to name the system they’re in and disrupt it – why not? What’s the worst that could happen?

We’d be interested to hear your thoughts on luck and what role, if any, you feel it’s played for you?

Luck has shaped my life in ways that were both painful and transformative. For me, luck hasn’t been a simple story of good breaks or misfortune. It has been a force that opened paths even in the moments that felt like loss. I experienced hardship early. Losing my mother at four and then my aunt soon after could easily be seen as bad luck, and for a long time it felt like that. Those losses changed everything. But in the middle of that grief, I was also given a different kind of luck: a family that refused to let me fall through the cracks. My cousins stepped in and raised me with love, discipline, and expectations that stretched me into the person I would later become. That foundation is luck too.

Luck showed up in the people who entered my life at the right time. My cousin Nella, who taught me discipline and confidence even while managing her own challenges. The labor organizers and movement elders who opened my eyes to what justice looks like in practice. Jahrik Browner, who saw something in me during a summer program and invited me into this work before I even saw it in myself. Rebecca Irby, who gave me permission to show up without shrinking parts of who I am. None of that was planned. None of that was guaranteed. Those encounters changed the direction of my life and my work.

Bad luck played a role too. Growing up in an underfunded school system. Watching loved ones navigate systems that didn’t respect their bodies or their labor. Seeing my community face disaster during Hurricane Irma. Those moments didn’t feel like luck at all, but they pushed me toward organizing. They taught me early that I couldn’t wait for help to arrive. They taught me that community is the first responder. They taught me that leadership grows out of necessity, not titles.

If I’m honest, my journey has been a mix of both kinds of luck. But what has mattered most is how I responded to each moment. I didn’t control the losses I faced, yet they sharpened my empathy. I didn’t expect to meet mentors who would open global doors for a kid from Savannah, but I was ready when it happened. I didn’t plan to go from marching in the streets to mentoring youth at the United Nations within a year, but preparation met opportunity, and that turned into a kind of luck too.

So when I think about the role luck has played in my life and work, I see it as something layered. I wasn’t lucky because everything went well. I was lucky because even the difficult parts carved out a capacity for purpose. I was lucky because people believed in me at crucial moments. I was lucky because I learned early that community is a form of wealth. And I was lucky because I refused to let the world’s expectations define my limits.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jxmsorawr/

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jimmie-henderson-b-s-178b99261

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@jimmietv8540